I’d been meaning to reread Watchmen for years now, but I didn’t feel like I liked the book enough to spend money on it, and it was always checked out at the library. Then, lo and behold, it was on the shelf a few weeks ago. A part of me wants to write a lengthier piece, and may at some point. Here, 500 words or so.

I’d been meaning to reread Watchmen for years now, but I didn’t feel like I liked the book enough to spend money on it, and it was always checked out at the library. Then, lo and behold, it was on the shelf a few weeks ago. A part of me wants to write a lengthier piece, and may at some point. Here, 500 words or so.

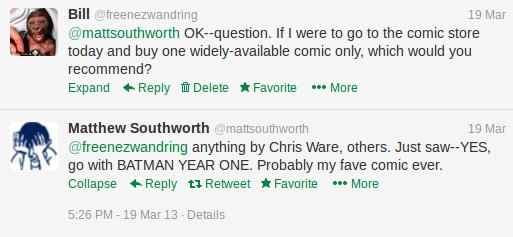

My first take on Watchmen, borrowed from a friend about a decade ago after I’d first gotten into comics, was that its reputation greatly outweighed its value. I had heard “greatest comic ever” from any number of people, and once I’d finished it, it was clear to me that those people were simply repeating to me what any number of people had told them. It was as if there needed to be a greatest comic ever and Watchmen was in the right place at the right time and so took the title. My second read has confirmed that first impression.

I’ve written about Moore’s Swamp Thing elsewhere and all of the basic critiques of his writing there were really expressions of what I’d felt upon that first read of Watchmen. What became clearer on this second read, however, was just how full of holes he is as a writer, or rather how wide the gaps are in his understanding of the world as it expresses itself in writing. Moore gets plenty of stuff right, to be sure. As a critique of superhero comics from within, the work is brilliant. Moore is a guy who–it seems to me from the outside–has an understanding of his medium that few likely can equal in sophistication, however one may disagree. No need to over-rehearse the details, but Moore very clearly exposes the fascist implications of the genre. Watchmen is genuinely meta, and from a time–late 1980s–when meta remained semi-hip.

Likewise, the comic is one of the finest documents of British/European Center-Left Cold War nuclear angst of which I know. Outside of its place inside comics, this is probably its chief importance as literature generally. As the Cold War has ended outside only a few right-wing think tanks, the possibility of nuclear annihilation has faded from public consciousness, however real the possibility remains. So too, at the time of publication, the general discourse in the United States was all Reagan triumphalism. Falklands aside, there was more room in public for a robust anti-nuclear movement in England, possibly because England lay in the middle of the two nuclear “superpowers.” Interestingly, reading Watchmen in this light gave it a vitality where it might, in 2013, seem a relic. Moore clearly had passionate feelings on the subject, and his eggheadery needs all the passion it can get, as a tonic.

The flaw in the work is that Moore references things he doesn’t really understand. One example: Nite Owl’s ornithological article, “Blood From The Shoulder of Pallas,” at the end of issue #7. No actual 1980s academic journal would publish an article a) in the flowery prose of British gentleman historians of the late 19th century that b) questioned the whole premise of the academic discipline the journal represents. That’s not how journals work. It might have been a letter to a colleague. This is admittedly a detail, but from a guy who seems to want to be placed among literary titans, it is completely unacceptable. The work is littered with similar semi-understandings. I’ll get to those in depth later, maybe.

577 words, not 500. I gotta reel it in.